Caste and Varna are often used as if they mean the same thing — but they don’t. This mix-up has shaped how we view Indian history and society, often leading to confusion and half-truths. The Varna system described in early texts was never meant to be a rigid, birth-based hierarchy. What we now know as the caste system came much later, influenced by centuries of social and political change.

In this post, we’ll break it down clearly:

- What Varna originally meant — and how it worked.

- How Jati (caste) developed and became hereditary.

- Where discrimination entered the picture — and how India addressed it.

- Why understanding the difference still matters today.

Quick question before you read on:

When you hear “caste system,” do you think it’s something ancient that never changed, or something that evolved over time? Drop your first thought in the comments.

Table of Contents

The Varna System: What It Really Was

When most people hear the word Varna, they immediately think of caste and colour — but that’s a misunderstanding that came much later. In its original sense, Varna meant a type or category of role in society, not someone’s skin or family name. It was a way of organizing work and responsibility in early India, long before rigid caste lines appeared.

Ancient texts described four broad Varnas: Brahmins who handled knowledge and rituals, Kshatriyas who took care of defence and administration, Vaishyas who traded and farmed, and Shudras who provided skilled work and services. The key point is that this was meant to be based on what a person did and what qualities they showed — their Guna (nature) and Karma (action). There are references in Vedic stories where people changed roles when they had the skill or aptitude. It wasn’t a fixed label you were born into.

The Rigveda’s famous Purusha Sukta uses these four groups in a symbolic way — comparing them to different parts of one universal being, not to a hierarchy of “high” and “low” people.

Sanskrit Verse (Rig Veda 10.90.12):

“ ब्राह्मणोऽस्य मुखमासीद्बाहू राजन्यः कृतः।

ऊरू तदस्य यद्वैश्यः पद्भ्यां शूद्रो अजायत॥”

brāhmaṇo ‘sya mukham āsīd bāhū rājanyaḥ kṛtaḥ |

ūrū tad asya yad vaiśyaḥ padbhyāṃ śūdro ajāyata ||

Translation:

“The Brahmin was his mouth, the Kshatriya became his arms, the Vaishya his thighs, and the Shudra was born from his feet.”

This is a metaphor of interdependence — not a command for hierarchy. Each part is essential to the whole.

Centuries later, the Bhagavad Gita clarified:

Sanskrit Verse (Bhagavad Gita 4.13):

“ चातुर्वर्ण्यं मया सृष्टं गुणकर्मविभागशः।

तस्य कर्तारमपि मां विद्ध्यकर्तारमव्ययम्॥”

cāturvarṇyaṁ mayā sṛṣṭaṁ guṇa-karma-vibhāgaśaḥ |

tasya kartāram api māṁ viddhy akartāram avyayam ||

Translation:

“I created the four Varnas based on qualities (Gunas) and work (Karma).”

This shows the original idea focused on what you do, not where you are born.

Why is this important? Because it reminds us that the Varna system started as a model of division of work, not division of worth. Over time, social and political changes twisted this flexible system into something rigid — and that’s where caste comes into the picture, which we’ll uncover in the next section.

What’s your honest reaction to this? Does it surprise you that the original Varna idea wasn’t birth-locked? Share your thoughts below — you might find others have the same misconception!

Did You Know?

Some of India’s greatest sages and teachers, including Vyasa (the compiler of the Mahabharata), were not born into what we now call “upper castes.” Skill and contribution often mattered more than family background.

How Varna Turned into Caste (Jati)

Over time, the flexible Varna model slowly gave way to something far more rigid — the Jati system. Unlike Varna, which was originally about one’s qualities and duties, Jati referred to birth-based, endogamous groups where marriage usually stayed within the same community. This shift didn’t happen overnight. It unfolded across centuries, influenced by social, economic, and political factors.

As kingdoms grew, communities began to specialize in particular trades — farmers, potters, weavers, priests, merchants — and these professions often became hereditary. Social mobility declined, and people started identifying more with their community than their work. Over generations, this resulted in thousands of Jatis, each with its own customs, rules, and hierarchies, far beyond the four Varnas described in the early texts.

Then came the colonial period, which locked this fluid system into fixed boxes. The British, keen on administrative order, conducted detailed caste-based censuses and recorded Jatis in legal and land documents. This codification made caste a formal identity rather than a flexible one. Many modern divisions trace their roots not to ancient scriptures, but to these colonial practices.

So, the “caste system” we know today is less about the original Varna and more about this later, layered history of heredity, restriction, and political control.

Did You Know?

Many regions of South India had records of warriors becoming traders and traders becoming temple scholars — long before colonial times. History wasn’t always a straight line.

Reality of Discrimination – The Caste System’s Dark Side

While the early Varna concept aimed at cooperation and mutual dependence, history took a harsher turn. Over centuries, certain communities — often labeled as “Untouchables” and now known as Dalits and other marginalized groups — were pushed to the edges of society.

They were excluded from temples, denied access to wells, and forced into occupations considered “impure.” This wasn’t just about where someone worked; it became a matter of deep-rooted social exclusion and humiliation, passed down through generations.

India’s Constitution, after independence, abolished untouchability and made caste-based discrimination illegal. Reservation systems (affirmative action) were introduced to uplift historically oppressed communities and give them access to education, jobs, and representation. Yet, as we look around even today, prejudice hasn’t vanished entirely. In some places, subtle barriers remain — in social attitudes, marriage preferences, and even employment opportunities.

This reality reminds us that while laws can change overnight, mindsets take time to transform.

Myth-Buster

Myth: “The caste system was always about untouchability.”

Reality: Untouchability, as practiced later, was not a universal ancient feature — it intensified during certain periods and regions, often due to socio-political factors, not scripture alone.

Breaking the Chains: Reform, Law & a Changing India

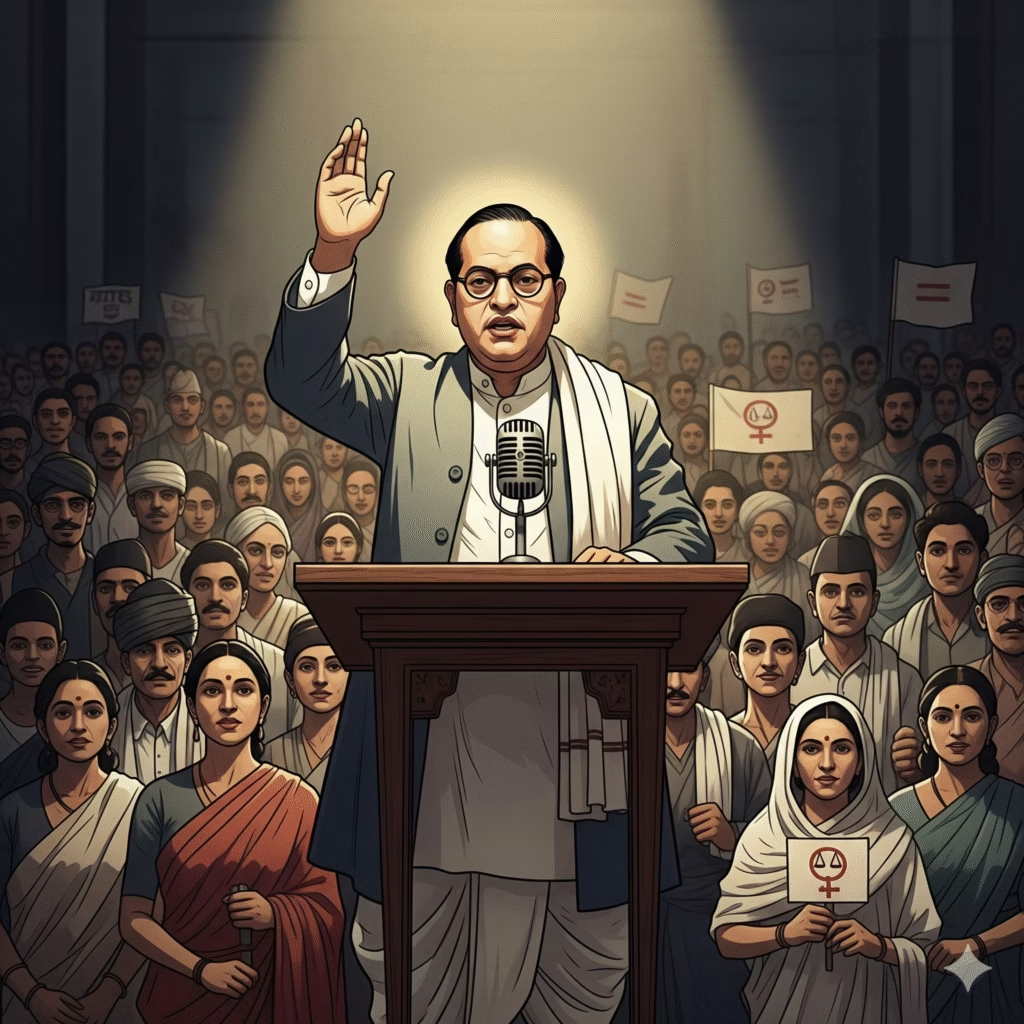

The story of caste in India isn’t just about oppression — it’s also about resistance and reform. From the 19th century onwards, voices of change started rising against this rigid structure. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, often called the architect of the Indian Constitution, dedicated his life to fighting untouchability and ensuring equal rights for Dalits. Reformers like Jyotirao Phule and Periyar E.V. Ramasamy also questioned age-old hierarchies, organizing movements that demanded dignity for all.

India’s Constitution took this fight further by outlawing untouchability and laying down strong safeguards against discrimination. Reservation policies in education and government jobs were introduced not as “favours,” but as a form of corrective justice — meant to level the playing field for communities historically kept out of mainstream opportunities.

Fast forward to the 21st century: the narrative around caste is evolving. Urbanization, globalization, and access to education have blurred some old boundaries, especially in cities. Dalit literature, films, and art are now powerful tools of expression, reclaiming identities once silenced. Yet, in rural areas, discrimination hasn’t completely disappeared. The conversation today is no longer only about oppression — it’s also about assertion, empowerment, and representation.

Did you Know?

Dr. Ambedkar publicly burned a copy of Manusmriti in 1927 to protest its regressive rules, marking a turning point in the anti-caste movement.

Key Differences – Varna vs. Caste at a Glance

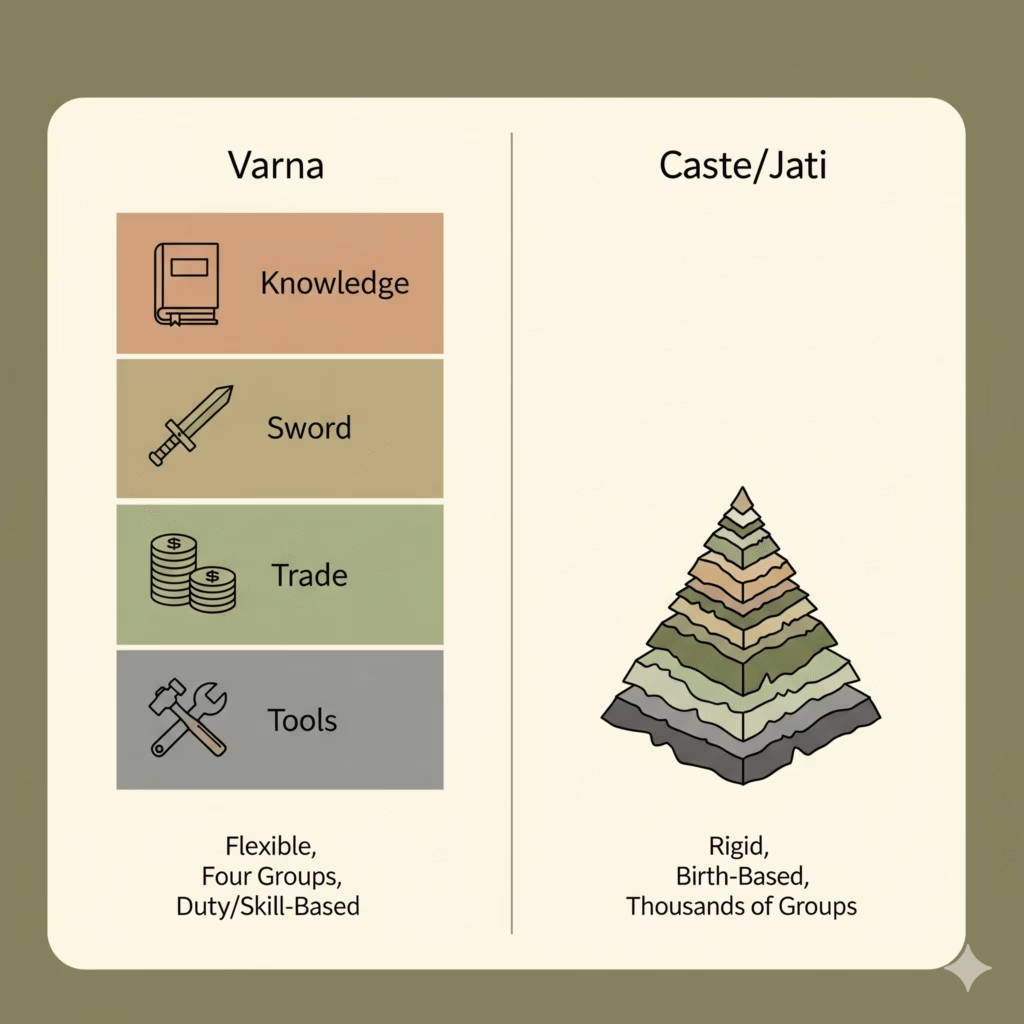

After tracing their histories, it’s time to address the most common confusion: people often use “Varna” and “Caste” interchangeably — but they are not the same thing. In fact, they differ in origin, purpose, and how they impacted society.

Varna was a conceptual framework from the Vedic period. It divided society into four broad categories based on aptitude, duties, and qualities:

- Brahmins (knowledge & teaching)

- Kshatriyas (protection & administration)

- Vaishyas (trade & agriculture)

- Shudras (service & craftsmanship)

This wasn’t meant to be a birth certificate stamped for life — texts like the Bhagavad Gita spoke more about one’s karma (action) and guna (qualities) than their parentage. Ideally, a person’s role could change with their skills, learning, or choice of livelihood.

Caste (Jati), on the other hand, evolved much later. It was not about what you could do, but what you were born into. Over centuries, these groups multiplied into thousands of local, rigid communities, each with its own rules for marriage, dining, and social interaction. Social mobility became rare, and hierarchy — often favouring some while excluding others — became the norm.

So while Varna was broad, fluid, and functional, Caste became narrow, hereditary, and often oppressive.

Did You Know?

The Manusmriti — often cited in caste debates — actually listed over 4,000 Jatis, most linked to occupations and local traditions, not divine command. Many of these divisions emerged gradually through trade specialization, migration, and regional customs rather than being rigidly set from the start.

Conclusion – Beyond Misconceptions

When we look back at the long history of India’s social systems, one thing stands out: Varna was never meant to be the same as the caste system we often talk about today. The original Varna concept described roles based on qualities, skills, and responsibilities — a flexible idea shaped by action and aptitude. But over centuries, with layers of social change, local practices, and later colonial policies, this fluid idea hardened into a rigid, birth-based hierarchy — the caste system (Jati).

Understanding this difference is not just an academic exercise; it changes how we view our past and how we talk about equality today. Knowing that much of the rigidity came from historical shifts — not from an unchangeable ancient law — opens the door for more honest conversations about social reform, justice, and inclusion.

History is complex, but clarity is empowering.

What part of this history surprised you the most — the original flexibility of Varna or the later rigidity of the caste system?

Share your thoughts in the comments below, and if you found this post valuable, pass it along to others who might want a clearer picture of our shared past.

For more deep dives into Indian history and culture, explore our archives or check out our digital magazine for exclusive features on untold stories of India.

FAQs – Frequently Asked Questions

Are Varna and Caste the same thing?

No. Varna was an ancient social framework based on qualities, skills, and duties, while the caste system (Jati) evolved later as a birth-based, rigid hierarchy with thousands of localized groups.

Did the Vedas support untouchability?

The early Vedic texts did not prescribe untouchability as a social norm. Practices of exclusion emerged much later due to regional customs, power struggles, and political influences, not as a core principle of Varna.

How did the British influence the caste system?

The British colonial administration formalized and codified caste identities through censuses, legal documentation, and administrative policies, making them more rigid than before.

Is the caste system still legal in India?

No. Caste-based discrimination was abolished under the Indian Constitution (Article 17). However, some social and economic prejudices still persist in certain areas.

What is the purpose of reservation in India?

Reservation policies aim to correct historical injustices by providing opportunities in education, government jobs, and politics for communities that faced centuries of exclusion.

Loving the info on this site, you have done outstanding job on the posts.

You have mentioned very interesting details ! ps decent site.

very nice submit, i actually love this web site, keep on it